TL;DR: Unless the tax madness unleashed by the Supreme Court decision last year is tamed, you will see many small online businesses like ours shut their doors.

By now, most people have probably heard of South Dakota vs Wayfair, the Supreme Court ruling the upended the decades long precedence of requiring a physical presence in a state or district to require the collection of sales tax. At this time, something like 2/3 of the states have enacted legislation that requires out of state or out of district sellers to collect sales tax if they exceed a gross revenue or number of transaction limit in a state or district within the state. Most states are going with greater than $100,000 in sales and greater than 200 transactions to trigger the collection of sales tax.

What exactly does this mean for a business like ours?

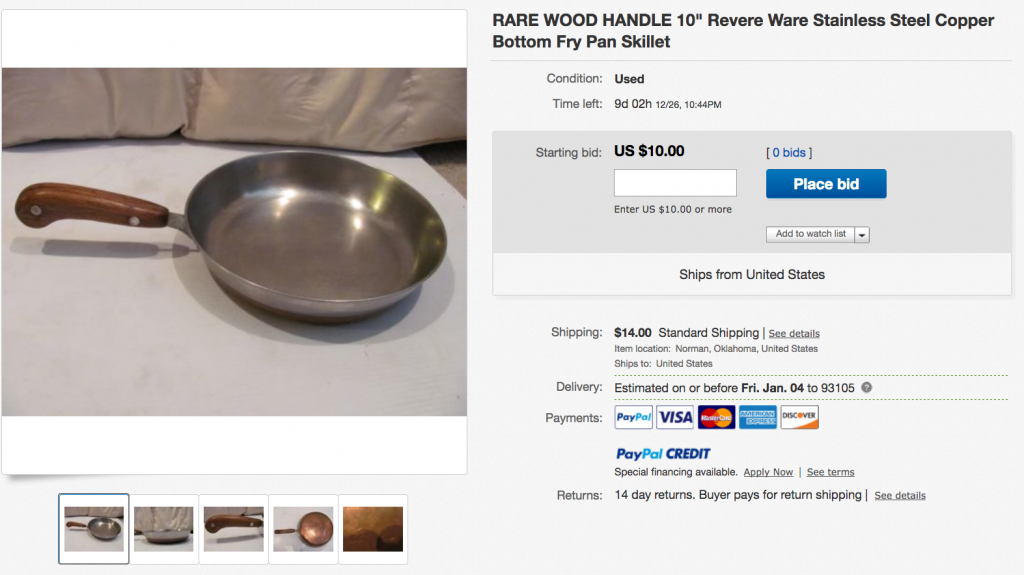

First, a little background. Admittedly, ours is a niche business and one done out of care and concern for the people who love and still use their decades old Revere Ware, like us. In other words, we aren’t primarily in it for the money. Having said that, making money off of this venture is a way to justify continuing to put significant effort into it. We’ve also spent considerable time to streamline the business so that it doesn’t dominate our lives for the small amount of profit it makes each year.

From our perspective, the difference between the two thresholds, $100,000 and 200 transactions, is also a little strange. Our average transaction total is $12.13; our parts are pretty cheap, and people tend to buy one or two. That means, 200 transaction is only $2,476, a long, long way from $100,000. It means that if we are unlucky, we just might pass that threshold in a few states or tax districts. (BTW, a tax district is any area that has it’s own special tax, like a state, city, or county.)

So when we look at the cost of compliance of the new tax regime, our main concern is simply whether attempting to be sales tax compliant will become incredibly burdensome, and there seems to be every indication that it likely will, unless things change.

Consider that there are more than 10,000 ta districts in the US. Assuming that every state adopts some kind of post-Wayfair decision sales tax regime, that means that we have to be aware of each and every sales tax jurisdiction and whether or not we have breached the threshold. In California, the moment you breach the threshold, you are supposed to register to collect sales tax THE VERY NEXT DAY, and collect tax from that point on. Can you imagine what it would take to pay attention to this and be prepared to register and collect taxes for 10,000 tax districts every single day.

Furthermore, there really aren’t any good methods to do this. Our sales data comes from two places, our sales as a third party through large retailers, and sales from our own website, which comes from our e-commerce platform. Neither has any good tools for dealing with this issue. That means we have to develop those tools ourselves. The data for our third party sales are very limited, so it isn’t clear if this is even possible.

Then comes the compliance burden of filing sales tax returns in every district in which we determine we have had to collect sales tax. Given that we may have only had to collect sales tax for a particular district for part of the year, starting at some arbitrary date, this makes it particularly onerous.

It currently takes us between 3-6 hours each year to prepare our single sales tax return. If it turns out we have to file 10 such return a year, that is 30-60 hours, or 3/4 to 1 1/2 weeks of work.

One justification for throwing open the doors to states collecting sales tax now, vs 1992 when the Supreme Court decision was made that limited this, is that online sales are all digital now and the cost of compliance is minimal. I can tell you, from the perspective of a small seller, this is not the case. The tools on the various e-commerce platforms that we’ve used, to just support making it easy to file a single state and district sales tax return, just aren’t there.

There is one more thing to consider, which could be much, much worse, than anything else related to what we’ve considered so far; some states will no-doubt be overly aggressive at pursuing online retailers for sales taxes. I’ve seen this happen in particular with California; they often will make assumptions and send out demand letters that then have to be meticulously defended to prove you don’t actually have a tax liability. This is potential more time consuming and costly than the compliance.

In short, I am very worried for the viability of small, online businesses if this sales tax trap is not fixed.

One possible solution is a streamlined sales tax system, where the same tax rules and rates apply within every jurisdiction across a state. This typically goes under the name SSUTA, or Streamlined Sales and Use Tax Agreement. While this would be an improvement over the current landscape, I still can’t imaging having to file 10 state sales tax returns every year.

Unless this is solved, I suspect that many small sellers, especially of niche products like ours, will simply close up shop. Some products will no longer be available, and sales will be consolidated among larger retailers that can handle the cost of compliance. Consumer choices will decline.