One of the most frequent questions we get asked is regarding handles where the butterfly wing-shaped piece of the handle spline has detached (either partially or fully) from the pot body. Here is an example.

We’ve never had a good answer to this question, so we set out to see what could be done.

Years ago, a brass spoon that my wife brought back from Thailand snapped along the stem when I tried to adjust the bend. At that time I was able to have it brazed back together, and the result looked pretty good. The stem was thick metal, and the brazing material was about the same color as the stem.

We posed this challenge to some experienced folks in an industrial metal-working shop, where lots of serious welding and brazing is done day in and day out.

Their first attempt was to weld the handle back on. As far as we can tell from the dots in the butterfly attachment (as can be seen above), the handles are spot welded on. This involves running a large amount of current from one side of the two pieces of metal to be joined, to the other. The internal resistance of the metal to electrical current causes the metal to heat up considerably, which fuses the metal pieces together.

However, it is often the case that when the spot welds on these type of handles fail, they create a hole in the pot body, so spot welding would not provide the best results in this case, as the holes would still be there.

Instead, they tried arc welding, with a consumable electrode. This is similar to spot welding, except that the electricity melts the consumable electrode, which leaves material behind to bind the two pieces together (and can fill holes).

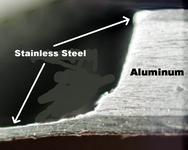

What they found was that the metal of the pot was just too thin to perform any kind of welding on.

So instead, they turned to brazing. Brazing is a process that joins two pieces of metal by melting and flowing a filler metal. Think of soldering electronic components.

However, again because of the thin nature of the cookware metal, it wasn’t possible to heat up the metal quite enough to really flow the brazing metal enough to get a really clean seam. The result is a functional, but somewhat ugly sauce pan.

For us, this leads to an obvious conclusion; it just isn’t worth it to try and repair separated handles. The work will likely cost you far more than a used replacement piece from eBay (of which there are plenty), and the results are less than satisfactory.

If you do want to attempt this, find a local weld shop or machine shop and ask them if the can braze (not weld) the handle back on.

Thanks go out to Patricia for sending us her damaged pot for this repair attempt.